Howe Gelb talks Tucson, staying alive and 25 years of Giant Sand

It is a balmy evening in early May in North London. We have gathered at a very small bar to see US singer-songwriter Howe Gelb (from Tucson, Arizona) play some numbers. Gelb has led his ‘alt-country’ band Giant Sand through the last 25 years, recording a vast back catalogue of music. In fact, if you include Gelb’s many solo albums and side projects (Sno Angel, The Band of Blacky Ranchette, OP8) we are talking well over a staggering 40 albums in total.

For the last year or so UK label Fire Records has undertaken a comprehensive reissue campaign to celebrate the quarter century of Giant Sand, lovingly reproducing the albums on thick heavyweight vinyl and gatefold CD presentations, each with witty, informative essays from Gelb himself, bonus tracks and where appropriate (the early albums) remastering.

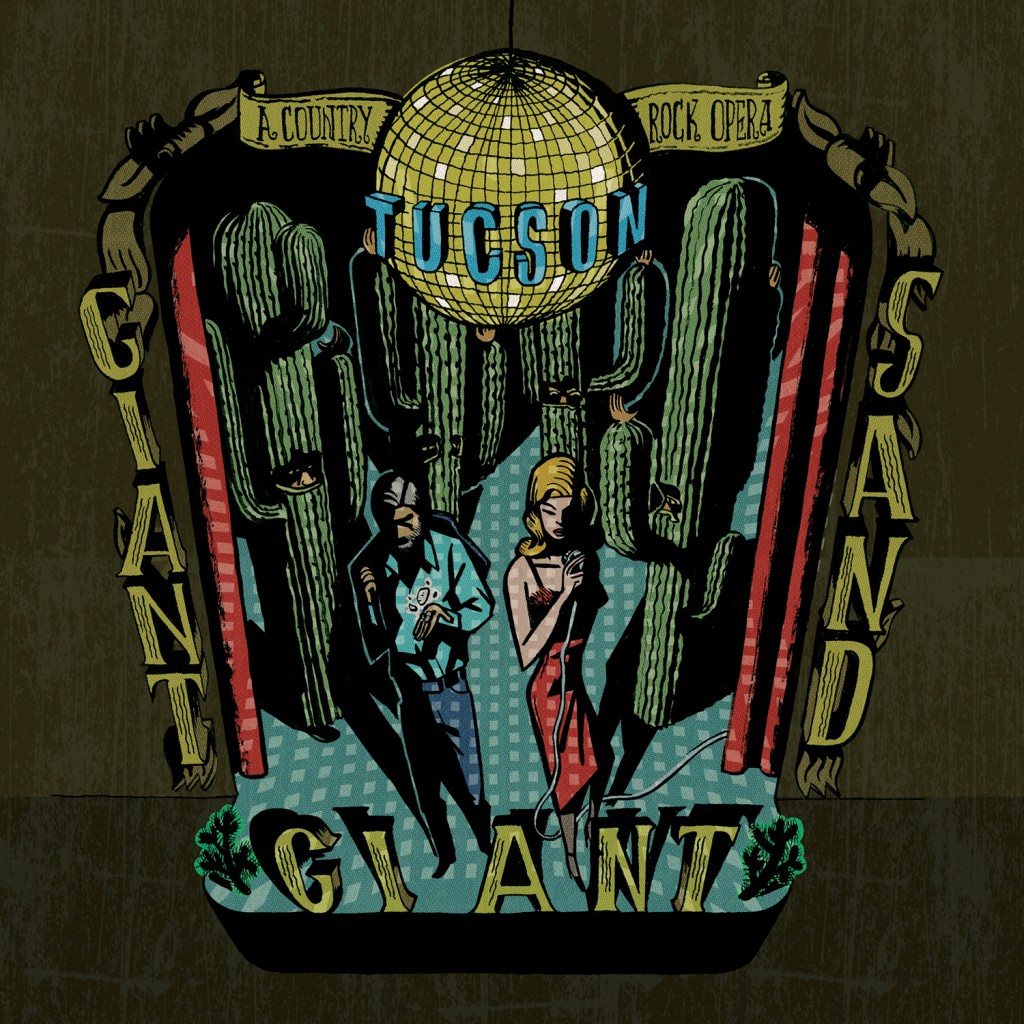

Gelb – now in his mid-fifties – is regarded as an elder statesmen when it comes to languid Americana, but he is still a fearless collaborator, working as hard as ever. Giant Sand has always been something of a musical collective, with different band members over the years and to underline this, the current line-up of all Danish musicians is supplemented with a string section and pedal steel player Maggie Bjorklund. A new album Tucson was released early this month with the band credited as Giant Giant Sand to drive the point home.

Back to the bar, and Howe Gelb chats away on the pavement outside to friends from the label, before a London black cab pulls up and a woman with dark hair steps out and immediately approaches him with arms spread, looking for a warm hug. The hug is dutifully received, and my companion informs me that the ‘woman’ is KT Tunstall [later that evening she will perform a song with Gelb to his simple acoustic guitar backing]. UK comedian Stewart Lee has also popped down to say hello, and there is definitely something of a buzz about the place. Tunstall ends up joining Gelb again on stage the following evening in East London, for a slightly larger audience. I make the mistake of not going along, and therefore miss out on seeing Led Zeppelin legend John Paul Jones handling bass duties for Gelb. Yes, things definitely happen when Howe Gelb is in town.

[vimeo video_id=”43177568″ width=”480″ height=”300″ title=”Yes” byline=”Yes” portrait=”Yes” autoplay=”No” loop=”No” color=”00adef”]

Before all these rock ‘n’ roll shenanigans, earlier in the day, I joined Gelb for a chat over some Greek food to ask him about 25 years of Giant Sand, the new record and the reissues.

SuperDeluxeEdition: How did the reissue campaign come about. Were you approached? Did you have a desire to get your albums back in to print?

Howe Gelb: I’ve always had a desire to be more organised, but I lack a bit of talent in that regard, so when James [Nicholls, who runs Fire Records] approached me about the back catalogue, I saw it as good timing. It marks the 25th anniversary of the first album and then I figured, finally, I’ll have the records all in one place so the kids can see what their dad did for 25 years.

SDE: How was the process of looking back, listening to old tapes. You once said ‘the past wasn’t meant to last’ but here you are celebrating it…

HG: It’s good to remember. If somebody dies the only thing you have handed down are the memories.

SDE: Fire records have done an excellent job with the presentation – some of the albums are presented as double 45rpm vinyl, a few are picture discs, and the CDs have great liner notes – was that care and attention aspect of the project important?

HG: That was a lovely bonus that I didn’t see coming. One thing we thought about beforehand was to remaster the early albums from the ’80s and early ’90s because the mastering was different then, and wasn’t geared towards CDs so much, with more thought towards cassettes and vinyl, so it was good to be able to go back in and tweak those old records. The down side of listening to those old records were the production values of the day. They were slightly abhorrent, and I would always fight against them. Meaning that the drums were always made too loud. I remember physically wrestling with the engineer, who was trying to ‘save us from ourselves’. As the tape was rolling by like a train, we were mixing those early records trying to yank down the volume of the drums, trying to figure out which was the drum fader and take off the gates and things like that.

SDE: The reissue of Chore Of Enchantment [released in 2000] has an entire bonus disc The Rock Opera Years – what’s the history behind that?

HG: That record was recorded with three producers. The first one was my dear friend John Parish. It was the first time we’d worked together. We’d set it up way in advance but it turned out to be only a couple of months after my best friend Rainer died [Rainer Ptacek was an East Berlin born musician who moved to America as a child – he died in 1997 from a brain tumour]. So I was damaged goods. Nobody knew I was, nobody could tell I was. So I would hear things and I could that it was not what I wanted to happen. The other problem was the band. I wanted more being put into our music and I wasn’t hearing the band put everything into the songs the way they used to. John [Covertino, the drummer] was actually good with that, but Joey [Burns, bass player] was like he wasn’t all there…

SDE: This was the period where their Calexico side project was gaining momentum?

HG: Exactly. They were starting to split away, but Joey was keeping it very hidden at the time. He wanted it so badly he kept it very close to his chest, so nothing could get in the way of it, whatever that could be. But that sonic paranoia started to drive a spike of division between us, because I had no idea what he was planning or doing or thinking. But on some of the sessions it sounded to me like he was phoning in his parts, which was a shame because he was such an important part of the band. He played beautifully and brilliantly on the earlier records when we were together. All I knew was that my best friend had just died, and I can’t hear myself, I hate my voice and nothing sounded right. It should be better than it is. So John Parish sadly had to suffer through all that. Later we went on to work with Jim Dickinson. That was the label’s idea to continue the process, and that was really a special time with Jim. And it was then that I came out of my writer’s block. I’d never had that before, but after Rainer died I wasn’t really coming up with anything. A whole bunch of new songs then started to come to me, but Jim couldn’t handle all the new songs because he was only contracted only for a certain amount. So finally we used Kevin Salem. He was brilliant. He helped bring some pieces together that John and Jim had done, as well as new fragments, and fashion an album in an atmosphere that I thought was good at the time. That was Chore Of Enchantment.

SDE: So the bonus disc is mainly from the original John Parish sessions?

HG: Yes. And most of that bonus disc is a stunning album. The only song that is too long – and John had nothing to do with it – is Music Arcade. That’s a little out of place on it.

SDE: Chore Of Enchantment has gone on to be one of your most highly regarded albums.

HG: I was pretty wrecked from the whole episode. I found myself going out to Denmark a lot. Just getting out of town – too many bad memories – for almost ten years. Even though I was still living there [in Tuscon] I ended up playing with anyone, anywhere else. I’d find inspiration up in Canada where I put together that Sno Angel band with the gospel choir and all Canadian players, and then I found this whole new Giant Sand band in Denmark and I found these incredible flamenco Gypsy players for the last solo album [Alegrías released 2010] – that’s been the last ten years.

SDE: You seem to find it incredibly easy to find these new musical partners. Is that just because music is in your blood and likeminded spirits attract?

HG: It’s a sonic life-force. It’s just always been there.

SDE: You don’t have any fear of taking risks, do you?

HG: [Looks out towards the road near where we’re sitting] Crossing one of these streets, for an American, is way more of a risk.

SDE: Tell me about your new album, Tucson.

HG: One of the reasons why I wanted to call it Tucson was to celebrate coming back and meeting Tucson musicians again, because there are so many great ones there right now. More than ever. And they are all very young.

SDE: But you’ve still got the Danish musicians on there as well though, haven’t you? It’s a fusion of sorts.

HG: [laughs] I can’t ever give anybody up!

SDE: You have something like 10 people in this new band – logistical nightmare, or just great fun?

HG: The playing is really great fun, but the travel arrangements is the logistical nightmare part.

SDE: What is a ‘Country Rock Opera’? [the subtitle for Tucson]

HG: I’ve never liked the term ‘country rock’, so I was just intent on redefining, so it’s basically a rock opera with pedal-steel and that gives it a country twinge.

SDE: When you come to start work on a new album – which seems to be quite often, since you record so many – how do you approach it? What drives the musical direction?

HG: I never over-plan it. I intentionally under-plan things. That’s something I learnt from the very first recordings.

SDE: You were something of a late starter when you recorded your first album in the mid-eighties. Was that an advantage, being a bit older with more life experience? [Valley of Rain, the Giant Sand debut, was recorded in 1985 when Gelb was in his late twenties]

HG: No, that was a drag. Maybe I wouldn’t have made so many records. If I’d started when I was 24 at least, it would have been a lot healthier, it would have made all the difference. But in Tucson, nobody knew what was going on, because it was such a remote place at that point. It had no information, it had no radio station. Most places had college radio – we didn’t have that. It had one tiny little record store that had punk records, but only a few copies, so if you got there on the wrong day they were gone, so we had to make up our own music. The whole Tucson sound comes from Rainer and me getting together in 1979. He was five years older than me, I was really young. He just wanted to make music that wouldn’t embarrass him 20 years later. So I followed suit and he taught me everything. Without even teaching. About family values, having kids, work ethics, everything. I was restless because my house was destroyed by a flood in Pennsylvania, so I was delivered out to Arizona – my dad lived out there – and then I met Rainer and it started all making sense. I was always drawn to traditional music but I didn’t know really how to wrap my head around it, but he would play it and I would learn it from him. I was really more into noise and experimental music, adding stuff that was new and had never been done before, because my ability was negligible.

SDE: But that became a positive and you turned it to your advantage…

HG: Yes, I made an ability out of my disability. That’s what punk rock did for everybody. So I found a cheap place in California to make music for 20 bucks an hour and we made the first album for 400 bucks. And I brought him in and thought I’ll produce you. You just set everything up and do what you do, and he did, and I thought I’d failed him, because – I didn’t tell him – but he didn’t play as good as he usually played at the weekend. But then when we put that record out, it was in the top ten records of the London Times that year. So alongside the ‘Stones and Peter Gabriel was Reiner’s Barefoot Rock [released as Barefoot Rock with Rainer and Das Combo in 1986]. So that taught us that there is something going on here. We just don’t know what it is. So at that point it was about where do we go to make records, and how do we get them out without selling our soul – and we both went our independent path, we never signed a contract.

SDE: You didn’t get ripped off by anyone, a big record label for instance. Was that just luck?

HG: No, it was just a matter of what was available to us. No one was coming at us, we didn’t know how to go to them. I came here [England] when I was 23 and played to somebody.. some label, I can’t remember, but it was some country stuff I was doing and it was 1980 or ’81 and they didn’t know what to make of it. They just dismissed it, and I left. So we worked with what we had we just kept going, and it was Andy Childs from Zippo Records – part of the Demon family back then – who heard it and said ‘I want to put this out’. And right before him was a French pirate called Patrick Mathé from New Rose [legendary French independent label] – he wanted to put it out. And Making Waves wanted to put out Rainer’s stuff, so we found a way to get it out there, with it just being on license. And all that is what started the thing that would eventually become the ‘sound’ of Tucson. That was the beginning of its reputation. We’d found a way to put the music out and from that point we didn’t go away. In the nineties things got much healthier with indie-rock and lo-fi thanks to Sparklehorse and bands like that and labels started to spring up that were more co-ops, indie rock labels.

And the other thing is that now nobody [in Tucson] thinks ‘I gotta go to L.A.’ to make a record, or New York to find a deal, or even Nashville. Back when Rainer and I were starting you couldn’t do that. You had to figure out a way to go out and come back, go out and come back… and figure out where do we put this and who’s going to care about it. But now the ripple effect all these years later is that everybody can just stay at home.

SDE: Has the changes to the industry – MP3s, iPods, file-sharing – affected you much?

HG: It’s give and take, because on the one hand it’s beautiful that things have changed. And that music is so available and word gets out in ways that it never could before. Videos used to cost £100,000 or more to make and they might only get shown on MTV and now you can do one for nothing and it’s on YouTube everywhere. That’s fantastic, man. I think it levels the playing field, as they say. But then for those of us who relied on the source of income – CD sales – we have to learn how to figure out new ways to roll with those punches. It’s not like I sold that many CDs [smiles]. MP3s are severely convenient, but they sound bad. Most young people don’t know how bad they sound until they go to a live show, and they go oh, this is much better…

SDE: Does the songwriting process come easy, the words and lyrics. This new Tucson album has a whole narrative structure going on.

HG: No I did it backwards. It was very easy [laughs]. That’s how I work, backwards. I did the songs first and came up with the story second.

SDE: Do you work to your own deadlines, or do you have people from labels, saying we need this by such and such a date?

HG: It’s changed over the years. In the old days I wanted to take care of the band, free them up from the day jobs – once I got freed up from mine. And the only way to do that was to make a new record. And this is one of the reasons why there is so many. So every six to eight months I would make a new record and get it out a month or two after that. And split the up-front money once the studio costs are paid off with the band. So they all had some money. And then we’d make money while we are on the road. That’s how we stayed alive.

SDE: Does it feel like ‘work’ when your recording and touring.

HG: Sometimes you get caught up in the workload and all that… but the trick is [big pause] anyone could do what I’m doing. The reason I have an audience at all is that the music is the kind of stuff they’d be doing if they made time for it. If you need a plumber to come to your house to fix your pipes, because you haven’t learned to fix your pipes, because you’re busy doing other things, then the system works pretty good. It’s the same with songs. If you need somebody to come to town and deliver some goods, you know… we can do that. That’s what we do.

Howe Gelb was talking to Paul Sinclair for SuperDeluxeEdition. Tucson is out now and can be purchased direct from Fire Records along with the Giant Sand reissues.

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

0